Inhabiting The Strike Zone

Maybe the real adversary of the owners isn't the players

Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

I squatted down to receive the first pitch of the bullpen. An 18-year-old freshman in an otherwise empty gym, I locked in on the right hand of the 6’5 pitcher — a former third-round draft choice — as he released his fastball.

I barely had to move my mitt. Strike one, I said to myself.

I was a walk-on at a D3 program. In fact, “walk-on” feels a bit generous. But I owned a cup and a catcher’s mitt — just enough to get me invited back to the next practice.

February practice in the suburbs of Philadelphia didn’t always resemble proper baseball. Under the same roof that the varsity basketball teams played their home games, atop the same thin layer of rubber that claimed more ACLs than all-conference honors, we were confined to a narrow end of the gym. It wasn’t unusual to pause activity to allow members of the track team to pass through or to retrieve an errant field hockey ball.

I had been practicing with the team for less than a month, doing more of what Bill Bryk would call retrieving. Catchers catch the ball; retrievers fetch.

In 1990, Chaon Garland was selected in the third round by the Oakland A’s. He was was released in Spring Training of 1994. One year later, he was pitching to me. That’s not how they drew it up in the A’s draft room, I can promise you that.1

The first overall pick in 1990 was Hall of Famer Chipper Jones. Next, the Tigers selected an All-Star first baseman who is in the news more now after his playing days: MLBPA executive director Tony Clark. Ninety-seven picks later, Garland’s name was called.

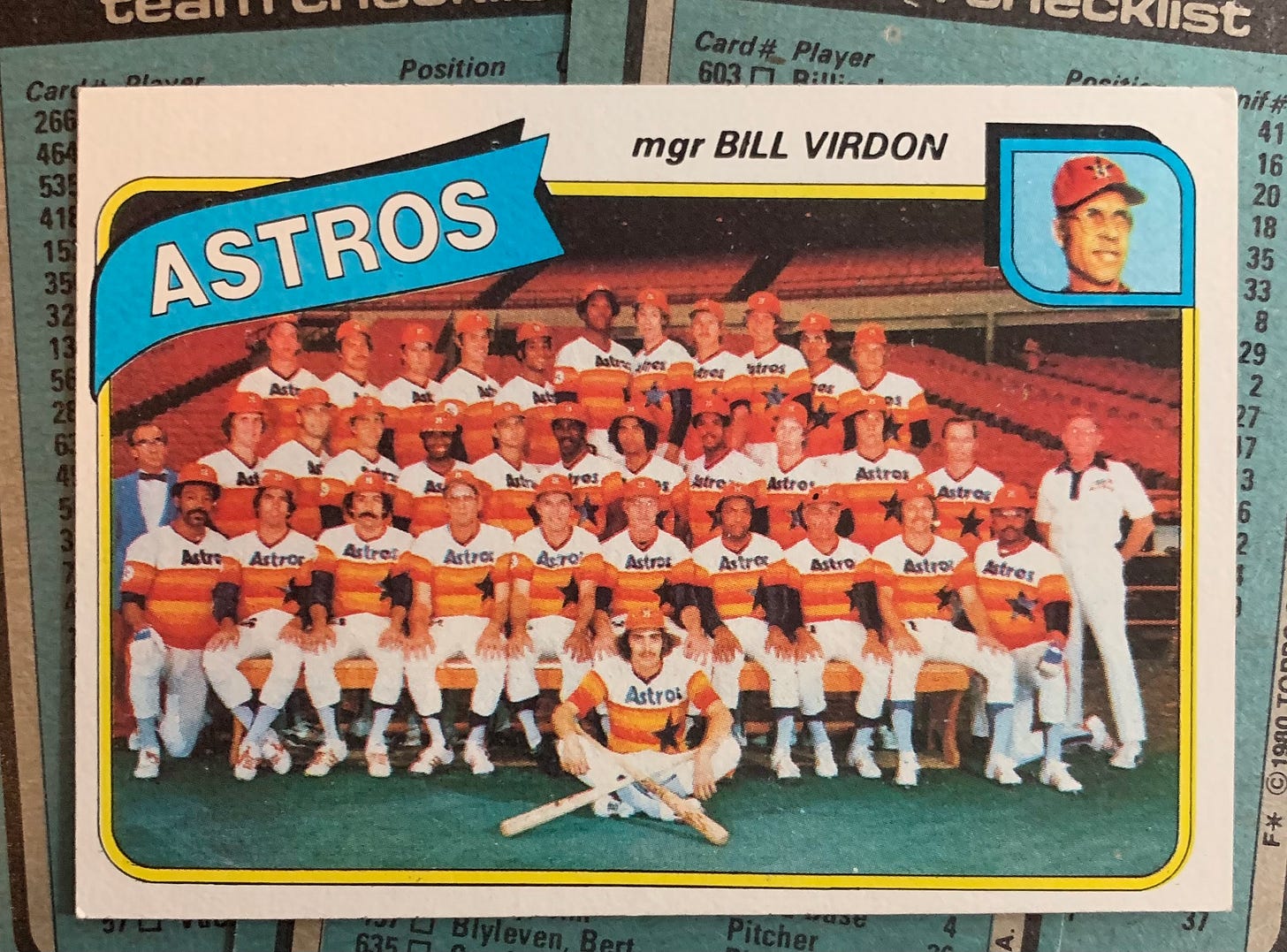

In early 1995, with the strike that had begun on August 12, 1994 still in effect, replacement players took the field when Spring Training began. Garland, tuned up after his February bullpen sessions, took the field for the Houston Astros when Grapefruit League games began.

Now, as the lockout enters its third month, a delayed start to Spring Training looks unavoidable, and I think the Opening Day is in jeopardy, too.

Recent reports concerning negotiations have focused on the minimum salary, a lower service threshold for arbitration eligibility, and a bonus pool for players who are not yet arb eligible. Luxury tax, service-time manipulation, and a draft lottery — as a way to combat tanking — are also major points of contention.

What’s the common thread in all of these issues? Money and the possibility of more money to come.

So far, negotiations have been a boring heavyweight fight. Both sides entered the ring flanked by oversized entourages, but once the bell rang, the two fighters have slowly danced in circles, occasionally throwing a jab while keeping their guard up.

The PA asked for $105 million in bonus pool money for players who have yet to reach arbitration (and therefore are making the minimum or not much more). The league countered at $10 million; the PA reduced its ask to $100 million. Please don’t tell me that’s progress.

Additionally, the Players Association wants arbitration eligibility to begin one year earlier — at two years of service — so not only are the two sides $90 million apart on the amount in the pool, they’re also about 125 players apart as to how many qualify for bonus consideration.

While lockout coverage generally searches for reasons for optimism, I’d remove the emotions and consider what really could be happening.

The issues widely reported upon today are the pawns. Both sides posture, expressing outrage and indignation over the other side’s failure to understand, in an attempt to curry public favor.

Consider the bonus pool: No matter how far apart the two sides are, it’s still only $90 million. Max Scherzer and Gerrit Cole will make almost that much combined in 2022 — if the season is played in its entirety.

My plea to you is not to follow that story. A $100 million pot for younger players? It’s a setup, a future concession by one party to gain something greater in a perceived compromise.

Would players rather have that money, or a restructuring of revenue-sharing practices that creates a greater correlation between a team’s profitability and winning?

Luxury-tax thresholds have served as a prohibitive salary cap. Intentionally non-competitive teams have lessened the demand for higher-priced (and valuable) free agents. The draft structure rewards poor results, which feeds the cycle of tanking.

Nothing in that previous paragraph benefits the players. Owners have no desire to change. Owners and the league have stood their ground, and the Players Association negotiates against itself.

Somewhere in these negotiations, though, deeper-pocketed owners are nervously watching their parsimonious peers, hoping that the cheap guys don’t ruin the racket for the entire bunch.

The negotiations are an awful variation on prisoner’s dilemma with the added function of time slowly bleeding both sides. Could it be that the gap between certain owners is equal to the current gap between the league and the players? Are the league’s histrionics — renewed with MLB’s most recent (rejected) request for mediation — simply a misdirection, diverting our eyes from the real problems at hand between smaller-market and larger-market owners?

I believe so.

After all, the owners are holding the keys. They have the power to unlock the season. And this time, there are no replacement players warming up in the gym.

Thank you for reading Warning Track Power. Subscribe now to have WTP delivered to your inbox every week without interruption.

The remainder of that session was no different. Every pitch filled a small perimeter never too far from the target. What began as the most nerve-wracking bullpen for me turned out to be the easiest. Years before the K-Zone entered our living rooms, Garland sketched a smaller prototype on that night with 35 fastballs.

This is one of the best pieces I’ve read yet about the current labor negotiations in MLB. (And I certainly have read enough about this subject.)