The Lives of Rule 5s

Stories from (and about) players whose careers changed overnight

“You probably remember me throwing. You know, I throw eighty-four miles an hour.”

It was an honest assessment from Joe Paterson, former left-handed reliever and present-day regional director at a national insurance company.

Following the 2010 season, the Giants did not add Paterson to their 40-man roster, thereby leaving him “unprotected” in the Rule 5 Draft. That December, he joined a group of players whose path to the big leagues accelerated overnight.

Designed originally so that teams couldn’t hoard prospects in the minors, the Rule 5 Draft is the last event of baseball’s annual Winter Meetings. It’s how Hack Wilson found himself on the Cubs. It’s how Clemente became a Pirate.

Usually the story doesn’t feature a Cooperstown ending, but no one really ever expects to win the Powerball either.

The parameters around the draft aren’t as complicated as they may sound. Eligible players in last month’s Major League phase must have turned pro at the age of 18 or younger in 2021 or at 19 or older in 2022. Any player selected must then remain on the Major League roster for the entire season.1

In 2022, under a new Collective Bargaining Agreement, the cost of a Rule 5 selection doubled from $50,000, where it had been since 1985, to $100,000. If the player is returned to the organization from which he was selected, then half of the cost is refunded. Baseball hasn’t had a bargain like that since Ten-Cent Beer Night in Cleveland.

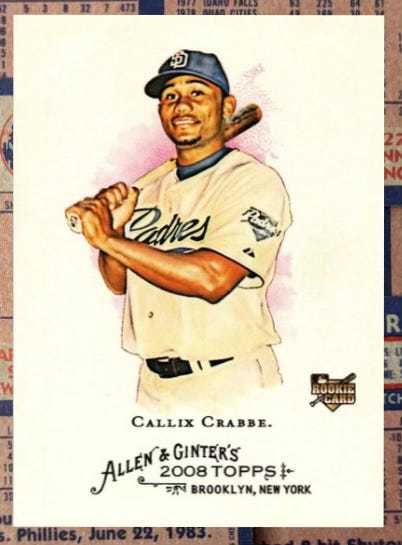

“I knew that if there was gonna be a path to get onto someone’s roster, it would most likely be via the Rule 5,” says Callix Crabbe, who found himself blocked in the Brewers system by big league second baseman Rickie Weeks and prospect Hernán Iribarren.

After a strong season in Triple-A Nashville in 2007, Crabbe headed to the Dominican to play winter ball. He recalls having additional motivation to perform: “My agent at the time… reached out to me and said, ‘Hey look, when you go down to the Dominican, if you continue to play well, there’s the potential that you could get snagged up in the Rule 5 Draft.’”

In a low-risk attempt to address a need on the fly, the Padres took Crabbe in that year’s Rule 5. Happy to be selected, Crabbe’s enthusiasm grew when he realized who one of his new teammates was. “I was even more excited because Greg Maddux, who was a childhood favorite of mine, was on the roster.”

The 2008 Padres had high expectations, which also motivated Crabbe. It was a roster that boasted a strong, veteran pitching staff, but the infield lacked depth.

“I remember coming into Spring Training, saying to myself that I had a chance… I was telling myself: Play as hard as you possibly can and just literally no fear. No nerves, just go get it done,” he says. Crabbe also credits his manager for encouraging him from the first day of camp.

“Coming in, Buddy Black was awesome to me. He told me that he saw me being someone like a Chone Figgins,” says Crabbe. (In an unexpected twist, Crabbe and Figgins are now good friends and golf buddies.)

Black encouraged his Rule 5 player to showcase his versatility, demonstrate his abilities, and steal a base when he could.

Crabbe also credits Tony Clark, who joined the Padres as a free agent for the 2008 season, with taking him under his wing. “He really provided me with the comfort and the ability to walk with some confidence,” Crabbe says of the current executive director of the MLB Players Association.

The final roster spot was down to Crabbe and infielder Luis Rodríguez, who had spent parts of the prior three years with the Twins. “It was pretty much a fight until the end,” Crabbe says. “We were playing an exhibition game in Anaheim and they ended up sending down Rodriguez. And so I felt like it started looking in my favor when that happened, but I still didn’t know… I was working out and [bench coach] Rick Renteria came in and grabbed me and, when I went in, KT, Buddy Black, and Rick were in the office, and then they broke the news to me.”

Ultimately, the Crabbe’s time in the big leagues with the Padres was brief, but his small sample size yielded some of the game’s most memorable splits:

He was 2-for-4 with a double and one RBI vs. Randy Johnson.

Against the rest of the league, he went 4-for-30 with no extra base hits and one RBI.

“I hit .500 against Randy Johnson, which is something that I will be able to take to the grave,” Crabbe says.

It’s worth noting that he drew four walks against six strikeouts during his six weeks in The Show. He showcased some of that defensive versatility, too, logging innings at second base, shortstop, left field, and right field.

This season, Crabbe will begin his fifth year as a minor league coach in the Pirates system. He’s currently a hitting coordinator, overseeing the complex league (essentially rookie ball) and the Dominican academy. He was previously the assistant hitting coach for the Rangers from 2019-2021.

Do those 21 games and 34 at-bats in the big leagues make a difference in his coaching world now?

“I think it does a ton. I think, one, it creates a level of trust... and, secondarily, it gives me a perspective to help [players] problem-solve because that was kind of like what I always had to do. I was never the type of player that just showed up and was able to do things quite easily, so I had to put together a system so that allowed me to show up every day and give myself my best chance to be successful… I talk to players regularly about developing consistent routines and being willing to allow your failures to be the feedback that you need to continue to get better,” Crabbe shares.

“And just for designing a progressive program that can help someone get better, I think having gone through mainly every level of baseball and then getting a chance to play in the big leagues — even though it was a short amount of time — it does provide me with a Rolodex of options that I can provide to them when it comes to a training environment.”

As is often the case with Rule 5 draftees, Crabbe was returned to his original team. I followed his progress that year back in Nashville and for the next few years as he bounced between Double-A and Triple-A in the Mariners and Blue Jays organizations. I wondered if the Rule 5 journey impeded his development. Facing this question, his tone shifts slightly, still friendly but more direct. This is clearly something he’s given thought to:

“I think it was a perfect opportunity for me. Where I think I fell short is, once I got back to the minor leagues, I did not reconnect with any goals. I had one basic goal and that was to try to get back to the big leagues, but I didn’t necessarily come back with a great structured plan, so that’s what I can leverage as a coach. I got back down [to the minors], and I thought it was all about performance. I just gotta do well to get back to the big leagues, and that is why I didn’t.”

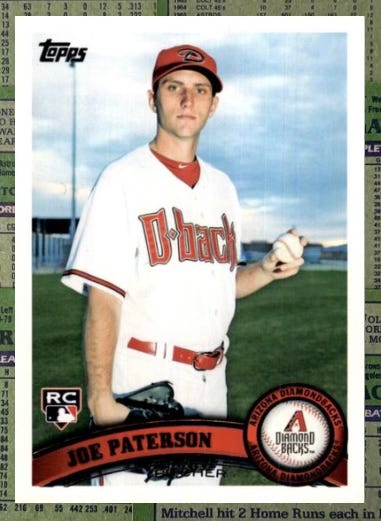

Joe Paterson

The Rule 5 Draft wasn’t on Joe Paterson’s mind when he woke up on the morning of December 9, 2010. He had only recently returned home from the Arizona Fall League, having spent six weeks in the bullpen of the champion Scottsdale Scorpions.

“That fall league team,” he remembers, “it seemed like everybody but three of us were put on 40-man rosters.” Indeed, on a team that included Bryce Harper, Brandon Belt, Charlie Blackmon, A.J. Pollock, Charlie Culberson, and some higher-profile pitching prospects, Paterson began to understand his value within the Giants organization.

“I do remember during that time just being like, ‘Oh man, that can’t be good.’ I also remember, honestly, I was super delusional. In 2010, I was the lefty in [Triple-A] Fresno for the Giants, and there was a time where it really looked like they needed a lefty [in San Francisco]. And I just could not figure out how that was not me. And then they went out and got Javier Lopez [at the trade deadline]. When I went to the Fall League, I ended up getting number 49, which was his number. And I remember thinking that can’t be a good sign either.”

Since the Scottsdale roster included Diamondbacks players, multiple scouts and other members of the Arizona front office watched many of the games. Paterson appeared in nine games that fall; it’s safe to assume that at least one D-backs official was in the seats each time he threw. Over 10 innings, he struck out 14 batters while only walking two and allowing six hits.

In an age before high-speed cameras captured and analyzed every event on the field, Paterson’s Fall League circumstances — that Giants prospects and D-Backs prospects were on the same team —serendipitously increased his visibility.

The decision to select Paterson is a look back in time, one that feels much longer than 15 years ago in terms of how the game has evolved. As with so many things, it’s all about timing.

Paterson became Rule 5 eligible during a transitional year for the Diamondbacks. Kevin Towers had just assumed control of baseball operations as GM. KT loved retooling bullpens and knew it was one of the fastest ways to improve a team. He also believed that you didn’t need to spend big to construct an effective bullpen; there were enough reclamation projects, waiver claims, veterans looking for one last chance, and live arms in independent leagues to cobble together outs. KT’s bullpens were a refuge for forsaken relievers and a collection of various arm angles, velocities, and outpitches.

At those 2010 Winter Meetings, the groundswell in the D-backs’ suite reached a point where KT was convinced that Paterson was the right pick. For a final blessing, he called his good friend and former minor league teammate Pat Casey. At the time, Casey was in the midst of a 24-year run as head coach at Oregon State, where Paterson pitched for two years — and was on the mound to record the final out of the 2007 College World Series.

I remember KT saying something like, “Hey Case, I’ve got you on speaker phone. I’m in our suite with the entire baseball ops team.”

Casey endorsed the left-handed reliever, speaking briefly on his character as a teammate, competitor, and human. KT hung up and announced, “Looks like Joe is gonna be a D-back!”

The suite erupted in a celebratory cheer. Was there a chance he could have been selected before we took him? Yes, but we were fairly confident that neither of the two teams ahead of us — the Pirates and Mariners — had interest.

In retrospect, that moment in the suite galvanized a front office. It was the shared experience that bonded longer-tenured D-backs and newer arrivals. Did it directly impact the ensuing 94-win season? I guess that depends on how much you believe in culture.

“I tell people when they ask, you know, what it’s like? Man, I could dream about playing Major League Baseball, but it’s one of the rare things that far exceeded, you know, times 10 what I ever thought it would be,” Paterson recalls. The thrill of the big leagues still hasn’t worn off for him, more than a decade after his last appearance.

His calling card — in a season in which the Diamondbacks and Brewers were on a postseason collision course — became his ability to neutralize Prince Fielder. After allowing an harmless single to Fielder in their first meeting, Paterson struck out the slugger in their next three regular-season showdowns. As an encore, he fanned Fielder once more in the NLDS.

The following year, Paterson entered in relief of Opening Day starter Ian Kennedy to face Giants lefty Aubrey Huff with two outs in the seventh. After getting ahead 1-2, Huff fouled off five consecutive pitches before grounding out to first baseman Paul Goldschmidt. Mission accomplished.

“And then I think I went… I don’t know… I went a long time without throwing in a game. I think it was a week-plus — and I wish I could get in a time machine and go back — but I remember it starting to get in my head, and then kind of thinking, ‘Am I going to have it when I go back out there?’ And then once I went back out, I couldn’t record an out. I felt totally different. And the wheels just fell off.”

Paterson remembers correctly; that next appearance came on eight-days’ rest. After three consecutive bad outings later in April, he was optioned to Triple-A Reno, where he remained for the rest of the year. He resurfaced very briefly each of the next two seasons.

In his final big league appearance, he mopped up in a loss at Coors Field, allowing four runs in one inning.

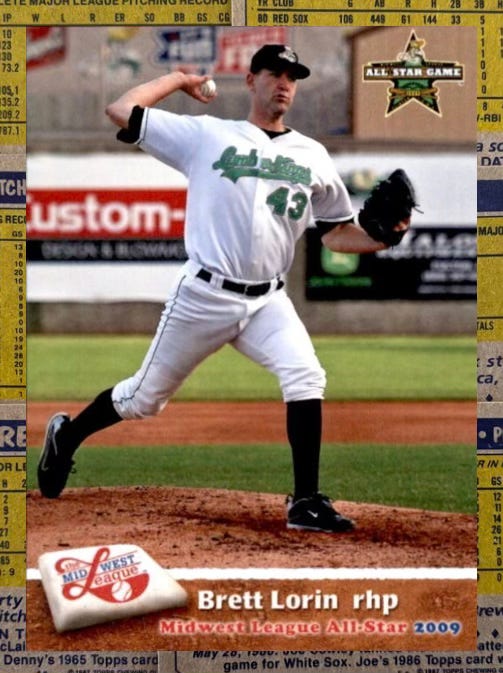

Brett Lorin

Like Paterson, Brett Lorin is also making a living away off the mound these days. Unlike Paterson, however, Lorin found himself on an established roster when his Rule 5 moment arrived.

“I needed a big break, and I was waiting,” Lorin admits. “Luckily, the Diamondbacks decided to take me. And it was the break that I needed in my minor league career.”

Lorin remembers learning that he had been selected. “It was early in the morning. We got the call. I was thrilled,” he says, recalling that morning in December 2010. Here’s where it gets good: “My dad ran in… I still lived with my parents at the time, it was the offseason… I was hopeful, but I wasn’t expecting anything. And all of a sudden — boom! — I get the call. I went from not sure where I stood after finishing in High-A to going to big league camp in the spring, which is a huge jump. This was the break that I needed. So at that time, it was very exciting for sure.”

Lorin had already changed organizations once. He was part of the return in a seven-player deal in 2009 that sent shortstop Jack Wilson from Pittsburgh to Seattle.

“You know what? I had a feeling I wasn’t a priority guy for the Pirates, honestly, because I was an All-Star that year, and they didn’t move me up to Double-A the entire year… You start to play GM in your mind. I saw other guys getting moved up. I’m like, I have great numbers this year. How is it possible that I’m not being moved up to Double-A? It doesn’t feel like there’s a plan for me here. In my mind, I was secretly hoping that I would get taken in the Rule 5 Draft because that was kind of my only way out.”

Lorin entered a clubhouse with much different expectations than what Paterson had encountered just one year earlier. After winning the NL West, the D-backs had postseason aspirations and a solidified bullpen with defined roles. “It was a veteran bullpen, and it was hard to crack,” Lorin says. He’s right; with established arms like J.J. Putz, Brad Ziegler, David Hernandez, and even Takashi Saito and Craig Breslow, the roster flexibility just wasn’t there like it had been for Paterson.

“I knew I was going up against some stud pitchers in general. But it was my opportunity, and, you know, it was a chance for me to prove myself.”

Lorin remembers his roughest outing of that spring, but at least now he can laugh about it: “I’d say the funniest memory is, we were playing the White Sox… and I gave up an inside-the-park home run to A.J. Pierzynski.” In that same outing, he struck out Paul Konerko, a moment that built confidence.

“That White Sox team had so much talent on it — like, they were loaded then — but it felt good to know I could get big leaguers out, you know. Obviously that outing wasn’t great, but, in general, it was a good feeling,” he says.

In the end, Lorin didn’t stick on the big league roster, but he takes pride in the fact that the D-backs — instead of returning him to the Pirates — worked out a trade to retain him. A combination of timing, injuries, and maybe — like Lorin said before — not being a priority player within the Diamondbacks organization prevented him from ever getting called up. Nevertheless, he’s grateful for the Rule 5 opportunity.

“This was the big break that I was hoping that would turn into something. Like I said earlier, it really went from sputtering in the minors to having a chance to make the big leagues that next year. You can’t ask for anything better than that.”

And there are 13 players who will enter Spring Training this year with that same shot.

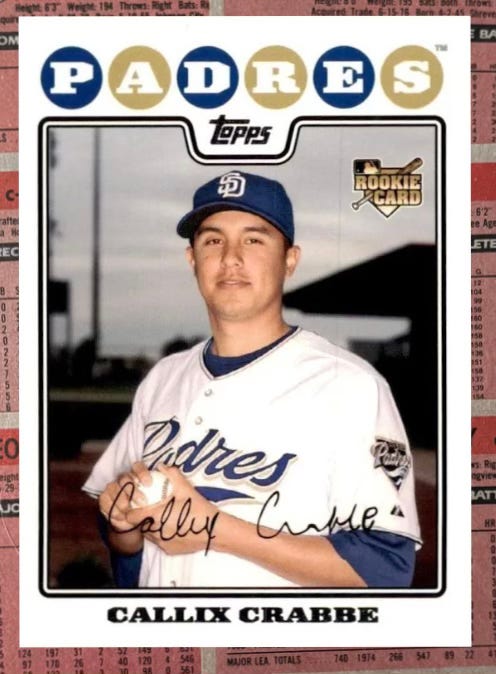

What’s it like to be a Rule 5 player? Check out the rookie card for Callix Crabbe and tell me if it looks anything like the player pictured in the card at the top of this story.

Callix Crabbe? No way! That’s Carlos Guevara, a right-handed reliever also taken in the 2007 Rule 5 Draft.

Technically, a Rule 5 player must be on the active roster for 90 days to shed his status for the following year. I’m happy to talk about teams manipulating the Injured List in an attempt to hide players, but we all have a busy day ahead.

Great stuff. I love hearing the stories about the moment that players got their opportunity to play in the big leagues.