A Spring Training Meditation on Jarred Kelenic

Allowing thoughts to come and go in Peoria

Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream.

Meditation can yield a sense of peace by narrowing and softening focus. It usually takes place on a yoga mat or in the privacy of a quiet room. Surrounded by 12,000 fans, I wasn’t expecting to achieve traditional results, but I was genuinely curious as to how the game would look and feel.

The public address announcer at Peoria Stadium read through the names of Seattle’s starting lineup. Though assigned as the visiting team, the Mariners were nonetheless playing in their Spring Training home stadium — the one they share with the Padres.

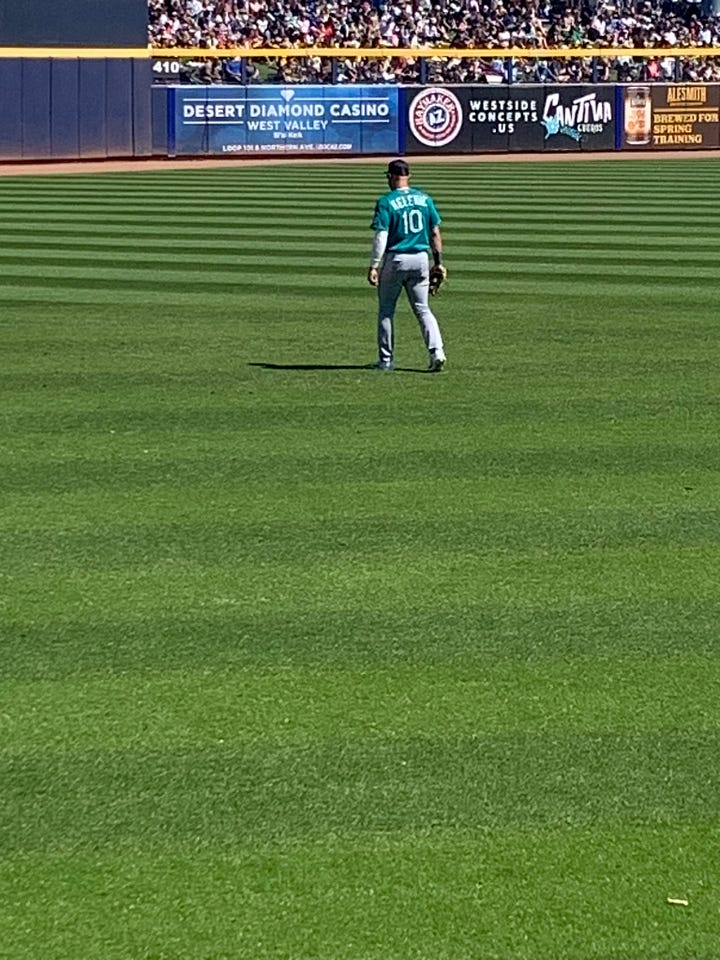

There was a noticeable applause from the Mariners fans, dressed in the aqua-like color proprietarily known as Northwest Green, when the name of the starting left fielder was called.

Batting seventh was Jarred Kelenic, a top prospect in the game from the day he was drafted sixth overall by the Mets in 2018. After horrific offensive struggles in 2021 and 2022, Kelenic has found success at the plate this spring. Tomorrow, all stats reset and he’ll need to recreate Cactus League contact in a much more meaningful setting.

But this past Sunday, he was still nestled in the sunny embrace of Spring Training.

I took a seat on the third-base side of the stadium, the same side as the Mariners’ dugout. I was beyond the infield dirt, aligned with shallow left field, many rows up from the action.

I looked for Kelenic in the dugout, but couldn’t find any sign of his number 10 among those uniformed players along the top step. Most of the jerseys I saw featured football numbers, no name above them to speak of.

My intention for the day was to watch only Jarred Kelenic.

There are hundreds games within the game to observe, if we choose to do so. We all can see different things when we gaze upon the field. I wondered what the game might look like with my eyes only on one player.

From a vantage point that didn’t offer a view of my target in the top of the first inning, I indulged in the rest of the action. I looked around the field in search of the action away from the ball. With a leadoff single, I was rewarded.

There were the middle infielders signaling coverage responsibilities to each other. There was the third baseman motioning to the shortstop, perhaps sharing a tendency of the hitter or a read off the first swing.

There was the baserunner, sliding safely into second base and — in one fluid motion — embracing the shortstop in a hug, the way that star players sometimes do, especially in Spring Training.

There was the shortstop rotating to cover third after the third baseman vacated the area to field a ground ball.

To meditate on Kelenic means letting go of all concerns created by such observations. It was time to focus solely on one player.

After a single by the Mariners’ five-hole hitter, Kelenic emerges from the dugout to assume his place on deck. The action, I should note, has been fast paced in this half inning. Padres pitcher Michael Wacha is working as though he’ll be flown on a private jet to San Diego the moment he finishes the day’s pitching assignment. Late March is not the time for dawdling.

Kelenic takes one dry swing from the on-deck area before the ball is put in play and the final out of the inning is recorded. He returns to the dugout, and I soften my focus awaiting his re-emergence.

From the outfield end of the dugout, Kelenic appears and runs at a comfortable pace to his place in left. A ball enters his radius. He catches it and throws it back in the direction of the left field foul pole. I do not watch the full path of the ball, losing it shortly after it leaves Kelenic’s left hand and finding it again as he catches it in the glove on his right hand upon return.

He makes a throw back towards the corner, and it looks as though the ball doesn’t leave his hand cleanly. I wonder if he bounced it.

Kelenic’s body language changes. He’s no longer expecting a ball to be thrown to him. He has turned to face the infield and begins to ready himself for the first pitch of the bottom of the inning.

He takes three or four deliberate steps in, and I suspect the pitch is delivered. My body is angled slightly away from the pitcher’s mound and home plate. I can see the color of the infield dirt out of the corner of my right eye, but my gaze is fixed on the left fielder.

Kelenic is always pacing, always moving. I resist the urge to look over to center field and right field and see if those defenders are doing the same. Instead, I rely on the memory of thousands of innings and understand that I am observing a highly active player.

Forward four or five steps, back four or five steps, a couple to the left, one to the right. He turns around to look behind him, a glance that isn’t to check out his distance to the fence but to observe the crowd on the berm and peek at the scoreboard. A new batter is announced and he moves several steps to his right, towards the left field line. He never looked towards the dugout or acknowledged anyone else in the field. He must know how to shade Jake Cronenworth by now.

He paces between the stripes in the outfield grass, two shades of green created by a skilled mower.

The next batter is announced — the third of the inning — and Kelenic takes a few steps back, assuming a deeper alignment. He reclaims much of the ground he has given, advancing towards the infield as, I assume, the pitch crosses the plate.

Kelenic is a sturdy presence in left field. He’s tall but not too tall, an inch or so above six feet. He’s muscular — more muscular than the baby-faced photos from his Mets days would have you expect.

I hear contact, and Kelenic barely moves. Finally, he is still. Somewhere else on the field, the third out of the inning is recorded. Kelenic runs in towards the dugout. He has some rigidity in his stride. His gait reminds me more of an NFL fullback than a five-tool prospect. I wonder if his baseball actions have adapted to his physical maturity.

He disappears into the dugout only to resurface soon after, helmet on and bat in hand. It’s a quick turnaround from left field to the batter’s box. Kelenic stands deep in the box, his left foot on the chalk that marks the back boundary of the area. His bat rests flat on his back shoulder.

The first pitch enters the hitting zone and he swings, fouling it away harmlessly in my general direction.

The pitch clock does not allow for over-adjusting between pitches. He’s back in the box, facing the pitcher, and takes an offspeed pitch for a ball. It’s fun to attempt to identify a pitch by watching only the final 20-30 feet of its flight.

The following pitch is a fastball that crowds him. Kelenic jumps back and is ahead 2-1 in the count. He lays off a breaking ball down and has worked this fast-paced at-bat in his favor. He swings at the next pitch and makes solid contact. He runs hard for the first 45 feet down the line, then eases into a jog. The ball beats him to the bag, and he never breaks stride, peeling off into foul territory, jogging along the grass, veering right as he gets behind home plate, and disappearing down into the dugout.

I stare at the Mariners dugout, but I don’t see Kelenic again until he jogs out to the field for the bottom of the second. He heads to his spot in left field and catches a ball that emerges from the left field corner.

At one point, he takes a couple strides to his right, makes the catch, spins and throws. Jarred Kelenic is having fun.

I want to put a Fitbit on him. Or maybe one of the wearable GPS trackers that soccer players use. How great a distance can he travel throughout the course of a game by simply preparing for the next pitch to be delivered? And how many steps is he losing because of the new limitations on the time between pitches? Will these rules save Kelenic’s legs, or does he need the movement? Might he be stronger in July because he has a little more time off his feet, off of spikes?

Kelenic is always active.

He signals that there are two outs by extending his left arm in a position parallel to the ground and flashing his index finger and pinky while the remaining fingers stay down. He points it in the direction of center fielder Julio Rodriguez and drops his arm when he seems satisfied that his message was received.

There’s a ball in play and Kelenic is already running towards his dugout, comfortable with the routine nature of the play. As he nears his destination, Kelenic accepts the offer of a fist bump by slapping his glove into the hand of a Peoria Sports Complex employee. A few paces later, the player disappears into the dugout.

The next time I see Kelenic, it’s the bottom of the third.

Kelenic starts out of the dugout and stops. He turns to say something to Rodriguez, then makes his way out to left field where a thrown ball escapes him. He walks after it — it had stopped and was only about six feet away — and swipes at it with his glove, securing it with the leather. He resumes his between-inning throwing routine.

He takes his glove off and secures it against his body as the first batter of the inning is announced. Kelenic adjusts the white sleeve on his left arm; it’s a compression sleeve that’s not a part of the Mariners uniform. Seconds later, his glove is back on his right hand, and he’s ready.

Kelenic makes a couple casual steps indicating that he read the ball off the bat confidently and is not involved in the action. With the announcement of the next batter, Kelenic moves closer to the right field line. At the crack of the bat, he charges in a few steps — quickly and briefly — before decelerating and returning to his original spot.

It’s a reaction to a foul ball, a short burst of energy inspired by contact. Some combination of the swing and point of contact told Kelenic that this ball might be headed his way. That it was a foul ball does not make Kelenic a fool for flinching. Quite the contrary, in fact. Years in the game — thousands of repetitions in the outfield — have trained the athlete to know what kind of swing might generate a ball in his direction. Sometimes the batter just misses.

One pitch later, Kelenic fails move whatsoever for the first time all day. The sound of the crowd reveals the outcome. It was a home run, and likely one that got out in a hurry. Kelenic remains still the way outfielders do for a no-doubter. Though the ball likely landed two hundred feet away from him, there is still drama in his stance, meaning in his motionlessness.

As I wonder how long he can remain still, Kelenic resumes his usual movements. For 15 seconds, he moves around a limited radius in left field. I wonder if he intentionally is keeping his left foot on the dark stripe of grass and his right foot on the lighter stripe.

On the first pitch to the ensuing batter, Kelenic throws both hands out in front of his immediately following contact. He didn’t see the ball. He has no idea where it is. There’s no panic, though. He recovers quickly enough to notice that the play is nowhere near him.

The midday Phoenix sun has betrayed many Cactus Leaguers over the years. The baseball gods protect Kelenic in this instance, though, and before too long he is jogging off the field exactly like he has each time before, slowing as he reaches the warning track area parallel to the infield dirt.

It’s another eight strides before he disappears, soon resurfacing after a quick equipment change from the other side of the dugout. Though he bats third in the inning, Kelenic is timing the pitcher from the on-deck spot. He works deliberately on the placement of his front leg, striding with his right foot and taking care of how he gets that foot down. Simultaneously, his hands drop low, settling just above the belt, and he displays a practice swing that no scout would recommend. What is he trying to reinforce through this bat path? He looks like he’s swinging into hurricane-force winds and trying not to lose his bat.

Kelenic returns to the dugout, perched on the top step, as the inning begins. It’s only one pitch until he’s on deck, eyes fixed towards the mound, and his practice swings in sync with the pitcher’s delivery.

He strides to the plate and rests his bat flat along his back shoulder. He swings at the first pitch and makes hard contact. Kelenic begins running with the pace and reaction of a hitter who’s not sure if he got it all. Will it clear the fence? His journey on the bases is also encumbered by a baserunner ahead of him who, with one out, is not going to commit to anything beyond second base.

Kelenic decelerates and changes direction. The ball has been caught. He jogs across the infield and disappears into the dugout.

At this point, the middle of the fourth inning, I decide to change my perspective. I head down closer to the field and end up against the fence in foul territory along the left field line. Kelenic is making his way out to his position, and he playfully gives someone a hard time for not being ready to play catch. He points up to the flags atop the batter’s eye in center field. The flags are blowing out, and now I imagine that he’s questioning how his opposite field fly ball didn’t clear the fence.

He pulls up some of the outfield grass and tosses it into the air. The grass didn’t carry enough either.

His warmup tosses conclude and he throws the ball into the crowd. He paces, as if he is superstitious over standing still for too long.

The home half of the fourth is over in five pitches. Baseball would never need a pitch clock if every game were played like it’s the final week of Spring Training.

Kelenic runs back towards the dugout, and I head to the press box where the game will unfold in front of me for the first time all day.

Kelenic isn’t due up until seventh this inning. He takes a spot on the top step of the dugout and rests both arms over the railing. He’s in conversation with a coach when the inning begins.

I find that, from my new seat, it’s difficult to focus solely on Kelenic. While watching Kelenic in the dugout, I can also see Julio Rodriguez lead off with a single. Where did my attention go as the ball was put in play? I’m guessing I followed the ball.

As with traditional meditation, though, it’s natural to have thoughts enter the mind. Acknowledge them and let them go. So, for me, goes Rodriguez, who is also removed for a pinch runner. Kelenic, who had reacted very little to the action so far, steps down into the dugout to receive the center fielder.

I shift my chair so I am squared up to Kelenic in the dugout. I watch him in conversation with a coach, unphased by a successful stolen base. But when a teammate is once again lifted for a pinch runner, Kelenic leaves his spot to meet him. High five? Fist bump? I can’t tell from my chair.

He soon returns to his spot atop the dugout steps and resumes conversation with the same coach.

While watching Kelenic, I see a sacrifice fly in my peripheral vision. I can feel the way in which I’m absorbing the game change because of the on-field “distractions” in my line of sight.

Kelenic leaves his perch with urgency. He’s now in the hole with one out.

I wonder how he was able to compartmentalize the potential of an upcoming at bat while talking to a coach. Were they discussing offensive approach, were they breaking down the current pitcher, or was it something less germane to the moment?

Kelenic appears on the top step by the home-plate side of the dugout. His helmet is on and his bat is in hand. His right foot is planted on the warning track dirt, one step up from his left leg.

He walks out to the on-deck area and, again, rests his bat flat on his back shoulder. It’s exactly as he stands ready in the batter’s box. He looks out towards the mound, returning to his routine of imagining himself in the box against the pitcher. As his lower half begins his swing, his hands load low. The awkward practice swing returns.

Kelenic has a youthful countenance — he is still only 23 — but over the past two seasons, he’s had little to smile about. In his Major League career, he is 84-for-500. That makes for easy math; Kelenic is a .168 hitter — fine if he was a pitcher.

His dry swings cry out “launch angle.” His bat path travels from low to high. But, perhaps, it’s also an exaggeration designed to keep his hands inside the ball. Perhaps it will help his bat stay in the zone longer. Perhaps it’s a escape route.

Kelenic drops his bat and runs behind the catcher, shaded towards the first-base side. A teammate is rounding third and there will be a play at the plate. Kelenic’s urgency to move into his teammate’s line of vision is much greater than the enthusiasm with which he motions for him to slide.

The runner slides in safely, and Kelenic claps once in approval.

He makes his way into the box now, and he watches a first-pitch curveball drop in for strike one. Nothing changes with his approach. The bat, hands, and lower half all work just as they did all day. He’s consistent.

He seems to be seeing the ball well and hitting the ball well, and consistency is really all anyone can ask for at this point. He’s ready for Thursday night, when the Mariners begin their season against the Guardians at home.

Of course, on Opening Night the M’s will face former Cy Young Award winner Shane Bieber, who is very much in his prime. The competition will be different than Cactus League matchups. A trusted routine will be what Kelenic needs to rely on when he steps in the box.

Back in Peoria, Kelenic takes a fastball for a ball, then tracks a curveball out of the zone. Prior to the 2-1 pitch, he calls for time — it’s granted — and steps out.

He takes another curveball — this one outside — and the count is 3-1.

With a pitch clock and limited opportunities to call for time, the pace of an at bat has hastened. It’s not too fast. It’s just streamlined.

The count in his favor, Kelenic takes a borderline pitch for strike two. He takes the full count offering as well, a cutter or slider that looks high and/or outside to me but is called strike three by the ump.

Kelenic takes a false step towards first base, anticipating the base on balls. His eye was true; however, his belief that, on March 26, the home plate umpire would rule to lengthen the game was misguided.

As he walks back to the dugout, inning over, Kelenic makes a half-hearted appeal to the umpire. He’s perturbed and begins to voice his disapproval, but he stops as quickly as he starts, perhaps realizing that now he, too, is one step closer to the regular season.

It was the middle of the fifth. Kelenic enters the dugout and seconds later, with a bag of gear in his left hand, exits. He’s in a full jog on the grass behind home plate, continuing down the first-base line. He catches up to four or five other teammates who were removed during or after the inning.

Blending into the aqua-colored crew of departing Mariners, Kelenic disappears towards the corner down the right field line.

It’s the bottom of the fifth, and I notice the score for the first time. The meditation is over. The season is about to begin.

WTP offers free and paid versions. Subscribe now and be part of the action on Opening Day.

Wow, what a unique perspective you took on this piece, Ryan. I felt so connected the whole time I was reading it.

Reminded me a little of George Will’s Men at Work, where in each chapter he analyzed one position by focusing in on one player.

Also reminded me of a book I read about a Celtics game 30 years ago, where the author spent the entire book in the one game.

Fascinating when you can focus in like this. And you told it so well.

There was just one thing I kept thinking: is there extended netting at the park? I was so worried that you were going to take a line drive foul ball to the noggin because you weren’t watching the batted ball!