Eye of the Beholder

Bob Gebhard has taken clever routes to first pitch

Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

If you don’t already subscribe (for free), please consider doing so today. And if you enjoy WTP, go ahead and share it.

It’s not everyday that you find a former big league general manager raking the dirt around first base on a substandard minor league infield, but on June 24, 2013, that’s exactly where I found myself.

I was in Mobile, Alabama, watching Bob Gebhard commandeer head groundskeeper responsibilities. I wondered how long it would be before he strongly suggested that I start tamping down the mound.

Geb, as he’s affectionately known to many and less affectionately known to some, had traveled to Mobile to scout the BayBears, who — at the time — were the Double-A affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks. If you haven’t figured it out already, Bob Gebhard was not about to allow an Alabama summer shower — or downpour — to stand in the way of a ballgame.

The BayBears manager was Andy Green, a former big league utility player who went on to manage the Padres from 2016-2019. I remember that Andy wanted to bang the game.

Andy should have known better. The less enthused to play he became, the more certain I grew that there would be a game at Hank Aaron Stadium.

Geb started taking inventory. How many rakes were in the shed? How much Quick Dry was on hand? How many members of the grounds crew were available to work on the field? I recall that the discussion involved a fair amount of angling on the part of those who weren’t interested in playing — some of the rakes were for leaves not dirt; there were only a couple people available to help on the field.

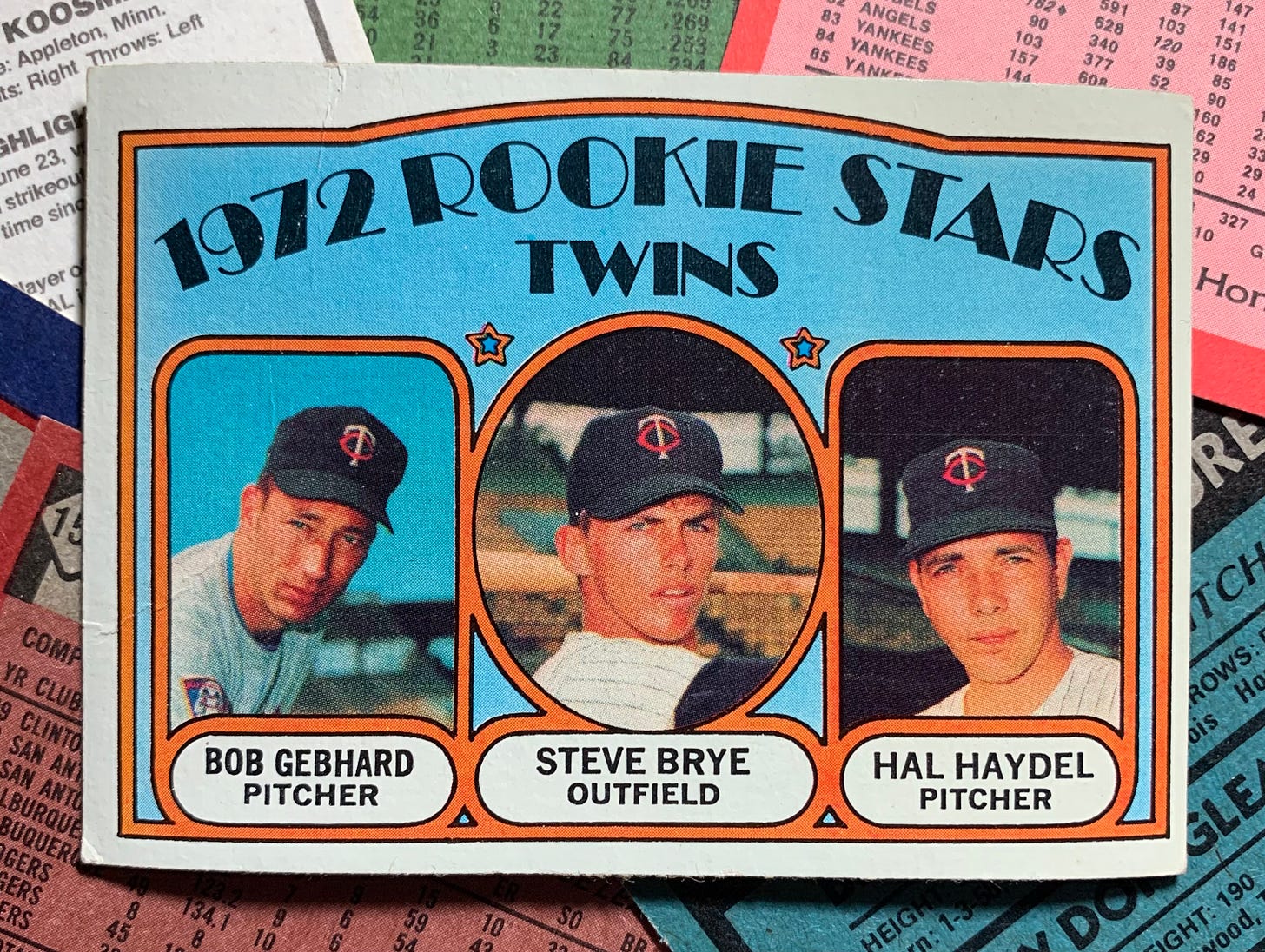

This only pissed Geb off more. After a lifetime in professional baseball — from pitching for the Twins and Expos in the early ’70s to holding a host of influential roles in player development with those same two teams to then becoming the Colorado Rockies first general manager — there weren’t many things Geb had never seen on or around a field. I was sure he’d watched baseball safely played in lesser conditions.

These were Diamondbacks minor leaguers after all, and it was our job to develop them. You sure as hell weren’t going to do that with a rain out.

So what’s the next move?

That’s right. Do it yourself.

Adorned in the traditional groundskeeper’s attire of a tucked-in polo shirt, khakis, and loafers, Geb got busy raking the area around first base. Of course, he didn’t put his cigar down either — this is minor league grounds keeping, not prison work, goddamnit.

And so, after a delay of one hour and fourteen minutes, the first pitch of the game was thrown.

Twenty years prior, though, Geb was about 1,400 miles northwest of Mobile in the football town of Denver, Colorado. Thinking about it now, for all the snow he had to deal with at Rockies home games, it’s no wonder that a summer storm did little to deter him.

With the All-Star Game hosted at Coors Field this week, I called Geb to ask him about his earliest memories of Major League Baseball in the Mile High City.

The story begins at Shea Stadium, where the Rockies franchise played its first game. As Geb put it, “We faced Gooden and Saberhagen — oh and two.” Indeed, the Rockies managed only one run over those two games in New York.

Coors Field didn’t open until 1995, so for the first two seasons the Rockies played at Mile High Stadium, the home of John Elway, Shannon Sharpe, Karl Mecklenburg, and Steve Atwater.

A ticket seller with the Twins, where Geb had worked immediately before taking the Rockies job, asked what he was thinking, moving to a baseball wasteland of rocks and sand. “You’ll never sell tickets,” the man told Geb.

Well, Rockies ownership had different ideas. Mile High could hold about 76,000 fans for a football game. For the Rockies inaugural home opener in 1993, additional seating was added to raise capacity to 80,000.

In center field, the Rockies were able to accommodate 500 of those additional 4,000 fans by setting up bleachers by the batter’s eye, the solid dark area beyond the center field wall that creates a clean background for the hitter to see the ball.

The batter’s eye, which was canvas, was laid down at an angle to allow for the bleachers. It was no longer serving its intended purpose.

Geb felt comforted by the fact that the opposing manager for the home opener was good friend Felipe Alou, who understood the greater significance of the day.

Geb, Rockies manager Don Baylor, Expos manager Alou, and the crew chief took a full lap of the field, discussing ground rules along the way. This is when Geb started to worry.

“If they get behind home plate and look out to center field and see this half-assed batter’s eye,” he says, “they might not let us start this game — and there are 80,000 people coming.”

Denver was new to Major League Baseball. Most of the Rockies employees were new to MLB.

Geb successfully distracted the umpire, keeping him from sizing up the hitter’s view from home plate. Meanwhile, Geb himself was left in the dark concerning a matter out by the bleachers.

It turns out that the misaligned canvas batter’s eye was tied to either end of the aluminum bleachers with rope to hold it up. On each side of the bleachers, a security guard was stationed. Each guard had a knife to be used for one purpose only: If the wind in the stadium became too strong, the guards were to cut the batter’s eye from the bleachers before the canvas backdrop acted as a sail and lifted the 500-person seating structure off the ground.

In that altitude, who knows how far it might have traveled.

Around the fifth inning of that home opener, the man from Minnesota who had doubted the potential of Major League Baseball in Denver called to check in. Upon learning that there were 80,200 fans in attendance, the man said, “Well, the second game is when you get a real sense of sales. You won’t do that well again.”

One day later, Geb placed a phone call to Minnesota. “You were right,” Geb told him. “Sixty-six thousand today.”

The Rockies drew almost 4.5 million fans that season, tops in baseball.

Thank you for reading Warning Track Power. Subscribe now to have WTP delivered to your inbox every Thursday.