If These Balls Could Talk

The stories inside a baseball

Welcome to Warning Track Power, an independent newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

Consider a baseball.

How about an official Major League Baseball — one with the commissioner’s signature on it?

Two pieces of very thin cowhide secured by 108 red stitches. It’s what we feel when we pick up a ball, when we play catch. We hold the outermost layer of the ball, giving thought to what’s inside only when reports suggest that a current crop is juiced.

Under the surface lives about one thousand feet of thread and yarn. Unwind these fibers and whittle them away to reveal a hard bouncy pink pill inside of which rests the core of the ball, the cushioned cork center, a phrase once proudly stamped on baseballs before the MLB logo replaced it.

The core contains the stories of every baseball. On the mantle, on the tee, in a display case on a desk, in a bucket, or falling out of the high sky to an infielder camped under it. Every ball has a story.

In more recent history, balls that had a chance for greatness — those that were hit for Miguel Cabrera’s 500th career home run and Aaron Judge’s 60th homer last season, for example — were specially marked before they were put into play to ensure authenticity.

Those are the balls whose journeys we hear about; the balls that immediately achieve six-figure values or a resting place in Cooperstown.

What about the rest? The routine plays — the groundouts, pop-ups and strikeouts — that are eventually fouled into the stands or tossed into the crowd after a scuff or scratch deems them no longer suitable for competition.

Recently, I shared the story of Padres broadcaster Don Orsillo handing my daughter a baseball outside of Petco Park after a game. Upon further inspection, the ball was not as pristine as I initially believed. It has a few signs of use — most likely it served in a few rounds of batting practice or crossed paths with a fungo before Orsillo claimed it.

In the moment, though — in my daughter’s clenched hand after a great night at the ballpark — it was flawless.

Shortly after that encounter, I shared the story with friend and former baseball agent Barry Axelrod. Baseballs, it seem, can also become time machines.

Axelrod took in the story and then shared his own. He was the same age as my daughter when he received his first baseball at a minor league game at Gilmore Field, former home of the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League.

Home of the Pirates’ Triple-A affiliate, Gilmore Field once stood in reasonable proximity to Canter’s Deli and The Original Farmer’s Market, two Los Angeles landmarks.

“I was 7 or 8 years old, hanging on the rail before a game — when games probably drew in the hundreds and not the thousands,” Axelrod recalls. “I was hanging on the rail sort of between the end of the dugout and where the Stars bullpen was down the right field line.” The boy who would one day represent Hall of Famers Jeff Bagwell and Craig Biggio was taking in pre-game practice.

“The pitcher finished warming up, and the catcher came walking by. He stepped to the side and handed me the ball. And I’ll never forget it.”

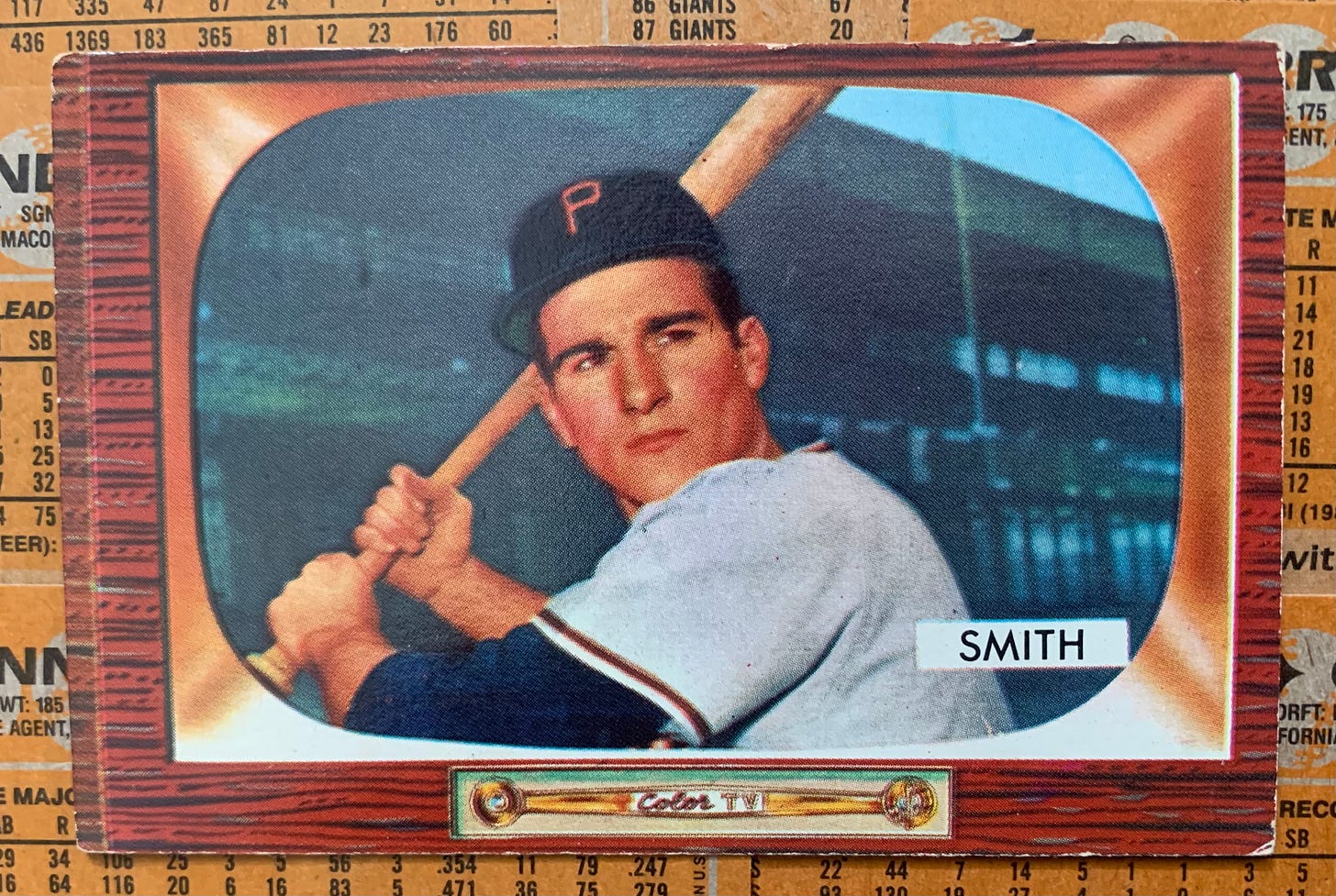

That catcher was actually infielder Dick Smith. In the era before Baseball Reference, the story would likely have ended with the catcher handing Axelrod a ball. But, now, we had a minor league mystery on our hands: Why was a shortstop who had spent parts of the past four seasons with the big league Pirates performing the duties of today’s bullpen catcher?

His career .134 Major League batting average might be a good place to start. Perhaps the real reason, though, was that the Stars were led by player-manager Bobby Bragan, the team’s starting catcher.

Bragan, who had played for Leo Durocher in Brooklyn the decade prior, was an infielder who found a home behind the plate. Perhaps because Durocher had deployed Bragan as a backup catcher, thereby adding value and longevity to his career, Bragan felt he could do the same for Smith.

(There’s a well-researched article about the life and career of Bragan on the SABR website that you can find here should you wish to dive deeper down the rabbit hole. Bragan led a fascinating life in baseball, learning under Branch Rickey and Durocher, managing Roberto Clemente, Roger Maris, and Hank Aaron, building a minor league system as the farm director of the nascent Houston Colt .45s, serving as president of the Texas League, and working as an assistant to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn.)

In Hollywood, meanwhile, Smith took the field alongside double-play partner and future Hall of Fame Bill Mazeroski.

There are hundreds of stories in the ball that Smith gave Axelrod. Luckily, we don’t need the actual baseball to tell them.

“I don’t know where it is,” Axelrod says. “It was probably used for Over The Line in the street.”

When I first asked you to consider a baseball, was there a specific ball that came to mind? Is there a ball you thought of during this story? Let me know!

This story is very boring compared to yours, but I've had an official Little League baseball on my desk for the past year. I just grab it when I get anxious. It's scuffed, and covered in blotches of caked dirt. I think it was once used in the bullpen that we call the street in front of our house. I'm sure many imaginary batters were struck out before school on weekdays when the boys said, "ONE MORE BATTER, dad."

June 24, 1956

Hollywood, Cal.

Dick Smith, at shortstop, is barely good enough for a

pennant winning club in the Pacific Coast League, - only barely.

He is a confirmed puny hitter, and it would be very easy to

over-estimate his running speed. He is not a slow runner,

neither is he a long strider. He may not really be as fast as he

is rated. The boy has no adventure as a base runner. He is

a nice person and the Hollywood club can possibly carry him for sometime to

come as an integral part of a good club. —BRANCH RICKEY http://tile.loc.gov/image-services/iiif/service:mss:mss37820:mss37820-053:08:0022/full/pct:100/0/default.jpg